| CONTACT US |

| HOME |

| FIELDSVILLE |

| FIELDSVILLE 2 |

| TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE |

| SAMPLE PAGE |

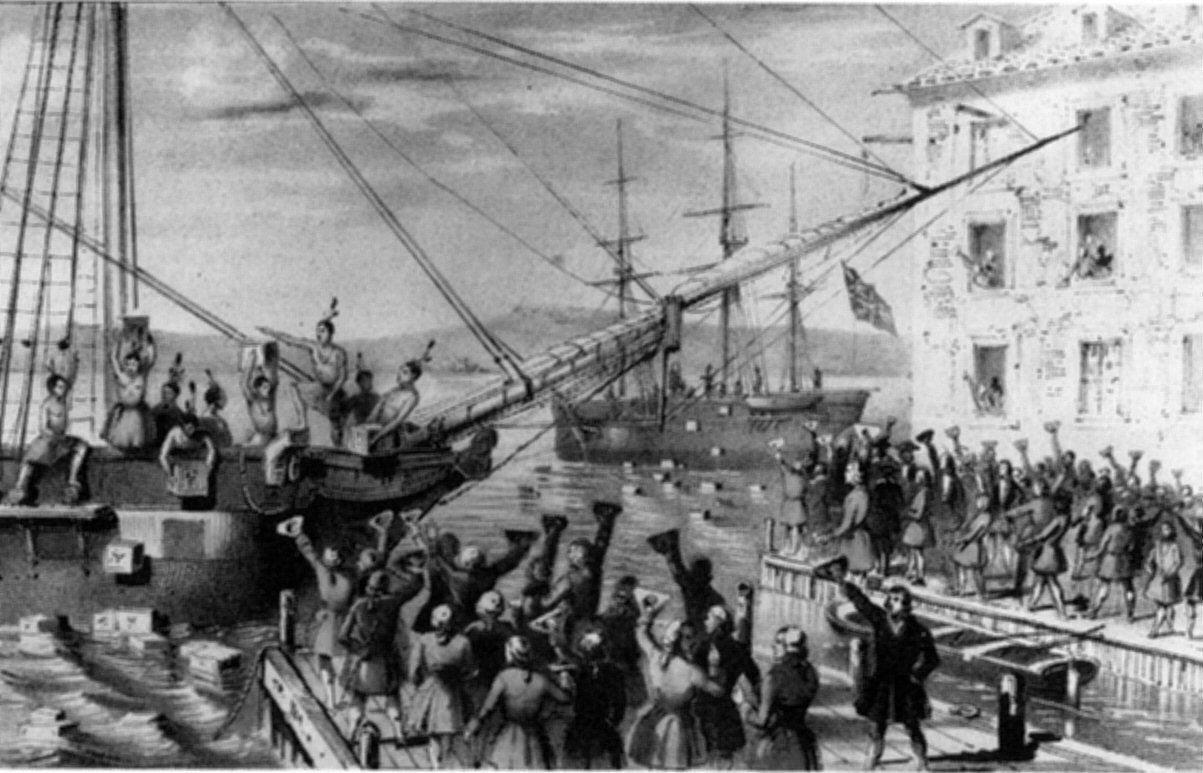

Quick Answer: The Boston Tea Party was the Bostonian's reaction to the East India Company's monopoly on tea exports to the colonies, and the tax on that tea. The tax was seen as Parliament's efforts to revise the plot to enslave the colonists by taxation. Some of the Sons of Liberty, dressed as Indians, boarded one of the East India vessels in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of tea overboard.

**** In England, Lord North had become the prime minister. By this time most of the Townshend Acts had been repealed by Parliament, but the Declaratory Act remained in tack. The tea tax, although very small, was resented by the colonists. Many Americans saw the tax as another claim by Parliament to the right to tax the colonists.

The East India Company was experiencing financial difficulties. In an effort to help that company, whose stock had dropped from 280 pounds to 100 pounds, Lord North gave that Company a monopoly on the tea exported to the colonies. The price of tea was to be reduced so that it would underprice any tea that the colonies could smuggle in. The Committees of Correspondence went to work attacking that new Act.

From the small tax on the tea, the East India Company's consignees (the men who received the tea and sold it, e.g., Governor Hutchinson's two sons and his son-in-law) would make a killing profit. Smugglers like John Hancock would be drastically hurt. Merchants in the colonies were warned not to handle the tea from the East India Company. The warning was heeded and the East India Company's ships were having difficulty unloading and selling the tea. In most ports the tea was unloaded and stored in warehouses and kept off the market. Boston ports refused to allow the tea to be unloaded. These ships could also not clear the ports until the duty on the yet unloaded tea was paid to customs.

On the evening of December 16, 1773, a group of the Sons of Liberty, dressed as Indians, boarded the East India ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor.

1. What did the colonists use for money?

Quick Answer: The colonists used various things for money, even sea shells. The scarcity of gold and silver in the colonies forced the various legislative bodies and banks to issue legal tender notes. Regardless of the value printed on them, the ability to redeem such notes determined their value. Some of these notes would only exchange for half of their face value. England refused to accept such notes for balance of payment on colonial imports. This practice contributed to the scarcity of gold and silver coin in the colonies. Eventually, the Americans copied the French system of using land as a standard of reserves upon which money was issued in paper notes.

**** During the 16th century small sea shells were used as money on the Atlantic coast. Settlers traded them for furs from the Indians. America was then on a fur standard, and using shells as a medium of exchange . Later, when the supply of furs ran low on the East coast, shells lost their value. The reserves that gave the shells value, the furs, were not readily available as the fur bearing animals moved west or became extremely scarce. In Virginia tobacco was lawfully admitted as legal tender as early as 1642. The tobacco standard lasted for nearly two centuries, almost twice as long as the gold standard in America. The gold standard lasted from 1879 until Richard Nixon's time in 1971. Tobacco was used sectionally, in Virginia, South Carolina, and Maryland. There were even currency notes backed by tobacco, with a picture of the tobacco leaf on them. This was long before the Surgeon General and the government's taxes made the weed less popular. Tobacco experienced Gresham's Law of bad money chasing good. It was the tobacco of lesser quality that was first exchanged, while that of better quality was saved. Later on quality standards were established for trading purposes. The exchange rate was automatically set by the market price of tobacco. As its price fell, relative to the British pound, so did its exchange value. In South Carolina, rice was also used as a medium of exchange. There were at various times other commodities used as money, including cattle, grain, whiskey, land, and during the Civil War, the South used Cotton Certificates . All of these were at one time legal tender for debt and taxes.

During the height of the mercantile system, England would only accept specie payment for the balance of trade. Colonial need for a medium of exchange was not England's concern. Colonial legislative bodies would issue notes of legal tender for taxation and debts, but these notes were not accepted by English merchants, or the Bank of England. Of the paper money circulating in the colonies, those notes of the Pennsylvania banks were the more respectable, Those of South Carolina and Rhode Island were the least respectable. Respectability, of course, depended upon the ability of the note to keep its value. They would lose value if too many were printed by the issuing bank, which would reduce that bank's ability to redeem them. The reason for gold and silver being the reserves upon which the bank notes were printed, was the relative constant supply of those metals. But, the scarcity of those metals, as we have seen, caused the use of other commodities to take their place. Paper was convenient, but subject to great changes in quantity by a too liberal use of the note issuer's printing press.

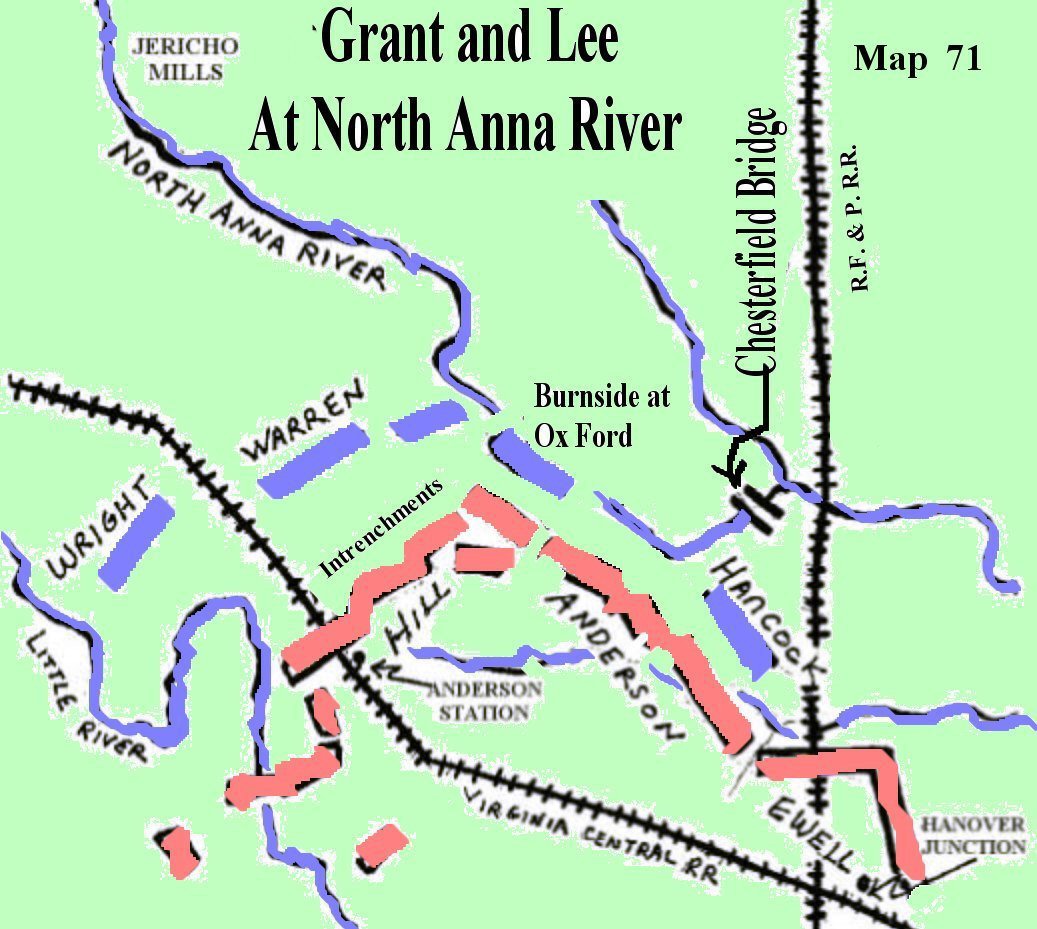

Quick Answer: Lee, having the inside track from Spotsylvania to Hanover Junction, had positioned his men on the south bank of the North Anna River. Grant's men started arriving on May 23rd, and crossed the North Anna at two locations. Warren and Wright crossed over at Jericho Mills northwest of Lee's forces. Hancock fought off some Confederate forces and would make his crossing at Chesterfield Bridge at the other end of Lee's lines. Still coming up, Burnside's corps would join in the next day's attack positioning his troops at Lee's center at Ox Ford. The Confederate batteries on the heights just across from Burnside kept him from being able to cross the river there. Lee's line of battle took the shape of an arrow centering on Ox Ford and pointing north. Grant's subsequent charge split his lines on the tip of the arrow. Just across the river from Lee's men. One of Lee's advantages in his position was that he could reinforce either flank with the other in short order. To do the same thing, Grant would have to cross the North Anna twice. Seeing this tactical error in time, Grant moved his army in a wide sweeping move downstream to Atlee about 12 miles north of Richmond.

**** Ewell started his withdrawal to Hanover Junction about noon on May 20th. Anderson followed with his corps about 4 hours later. A. P. Hill, recovering from his illness, reported that he could resume command of his corps. Lee instructed him to withdraw at night, unless Grant had pulled out sooner. Lee reached the North Anna by 8:00 a.m. the next morning. Ewell located his troop on the south bank of the river, and when Anderson arrived, he extended the Confederate line to Ox Ford, a mile and a half farther up the river. Lee's headquarters was set up near the junction of the Virginia Central and the Richmond to Fredericksburg Railroads. Breckinridge had arrived and was put into position between Anderson and Ewell. Pickett's division had also come up from Petersburg. Lee assigned that division to Hill's, covering his left flank against any attempt Grant would make there or at Ox Ford.

Hill arrived at North Anna on May 24, and shortly after that, Grant's troops started arriving. Some long range cannon fire was exchanged. Warren and Wright had crossed the North Anna and were advancing on Hill's position on Lee's left. The Confederate troops did not take full advantage of their having repulsed Warren and Wright's attack on Lee's left. The rebel troops were not used to fighting on the offensive, having been in trenches so long at Spotsylvania. Warren's men recouped and drove the Confederate troops back to the line at Ox Ford. A very hard rain and a setting sun allowed the unmolested withdrawal. That engagement cost the Confederates about 620 men, and they had inflicted that many on the North.

On the other end of the battle line, Hancock had launched an attack on the Confederate right at the Chesterfield Bridge, The bridge was quickly taken and Hancock could cross his troops over the North Anna there. Grant's next move was obvious to Lee. Grant would attack both flanks and try to envelope him on the south side of the river the next morning. Lee had avoided Grant's "mouse trap" by marching straight for Hanover Junction. Grant had known Lee's destination and advanced to Hanover Junction via the Richmond to Fredericksburg Railroad tracks. Now Grant wanted to envelope Lee's army and get to its rear. Accomplishing that might end the battles between the two rivals and quicken the end of the war. The next morning, May 24, Wright had crossed the river and was on Warren's right facing Lee's left flank. Burnside was up and ready to join the attack by crossing at Ox Ford. Hancock had made a dry crossing at Chesterfield Bridge and was ready to start a full scale attack. That morning Grant received good news. Sheridan would be arriving that day back from his Richmond raid. Burnside, however, had run into the Confederate artillery guarding the south bank of the North Anna. Grant ordered Burnside to reinforce Hancock and Warren on both of Grant's flanks and leave a division to contest Ox Ford. This was done, but much to the surprise of Warren, he was running into little or no resistance on Lee's left.

After chastising Hill for having not gobbled up Warren's repulse the day before, Lee had Hill form his corps' line from Ox Ford southwest to Little River with entrenchments that would hold Warren and Wrights attacks. Then Lee had Anderson form an entrenched line southeast from Ox Ford to within one mile of Hannover Junction. Ewell's men were moved southeast from there to a quarter of a mile beyond Hanover Junction. With this arrangement, Lee might flank Hancock's men on their left and destroy that corps before Grant could bring up reinforcements. By noon Ewell's men were entrenched, and the trap Lee had devised for Grant was ready. At this point in time, Lee's "intestinal problem" hit him hard. He had to take to bed at a time when only a Lee could make his plan work. One legged Ewell, the timid Hill, and the inexperienced Anderson could not be expected to make Lee's plan work. Lee was raging from his cot, he could feel the victory he had planned slipping through this fingers. Hancock proceeded with caution, and Warren did likewise on the other end of Grant's line. Both finally moved up to the trap that lee had set. Both Hancock and Warren perceived an attack, in spite of the trenches before them, and both started digging in against a possible rebel attack. Grant had inadvertently split his army on the wedge of the arrow shaped rebel line. Neither of Grant's flanks could reinforce the other without having to cross the North Anna twice, whereas, Lee could reinforce either of his flanks with the other faster and without the hazardous crossing of that River. Grant saw the tactical error that he had made and canceled the attack orders at once. His troops continued digging in where they were and stayed there all day and all night.

Finally, after taking a loss of nearly 2,000 casualties compared to half that of the South,'s, Grant ordered a withdrawal at sundown on May 27, and headed his army south some 18 miles from Hanover Junction. By the time Grant had crossed the Pamunkey River and headed for Atlee, Lee's troops were waiting for him on the south bank of the Totopotomoy Creek. By this time, Ewell had come down with the "same" ailment that had plagued Lee, and he was forced to take a sick leave. Now, much of Lee's army, two corps, four divisions, and sixteen brigades were being led by new leaders.